Mark Ehlen- MCR Staff

If you ask the typical car enthusiast what is the most difficult part of any restoration project, probably 9 out of 10 would say the paint job. The more informed would likely go deeper and say the body work under the paint is more important because without a good foundation for the color the paint will never live up to expectations.

That is correct of course but MCR would like to take you even one level deeper and that is to the metal work. Perhaps the reason that the metal work doesn’t immediately come to mind as a critical factor in a restoration is because, for many owners, sheet metal repairs are only thought to consist of fenders, doors, quarters and maybe parts of the floor.

That was partly true years ago when many of the cars MCR sees were “restored” for the first time but that is definitely not the case today. As you’ve just seen with John’s Cuda, rust damage can be extensive and found to have penetrated deep into all the various structures. Unlike hanging a set of quarters, removing many of these parts to either repair or replace them can seriously affect the structural integrity of the body.

With any body shell but particularly with unibody constructed cars everything is connected to everything else and they all rely on each other for support. If any one or combination of parts get out of place, knowing exactly where it or they are supposed to be can be difficult without some sort or reference point to properly locate them. If one part gets out of place everything connected to it will also be out of place and that domino effect can cause a lot of problems when the car goes back together.

Imagine getting to the point of finally reassembling your car only to find that the doors don’t fit, the deck lid gaps are way off and even some of the suspension parts won’t bolt on correctly. And all this at the point where it can’t be fixed without destroying your new paint.

Another reason that metal work might not be considered hyper-critical is perhaps because many still believe that most metal imperfections can be fixed with body filler. Evidence of that is clear most every time MCR gets another car body back from being chemically stripped. The “repairs” that they see that were covered in body filler are sometimes nothing short of astonishing. Sometimes the filler is so thick that it isn’t completely removed by the chemical bath as is the case with John’s Cuda.

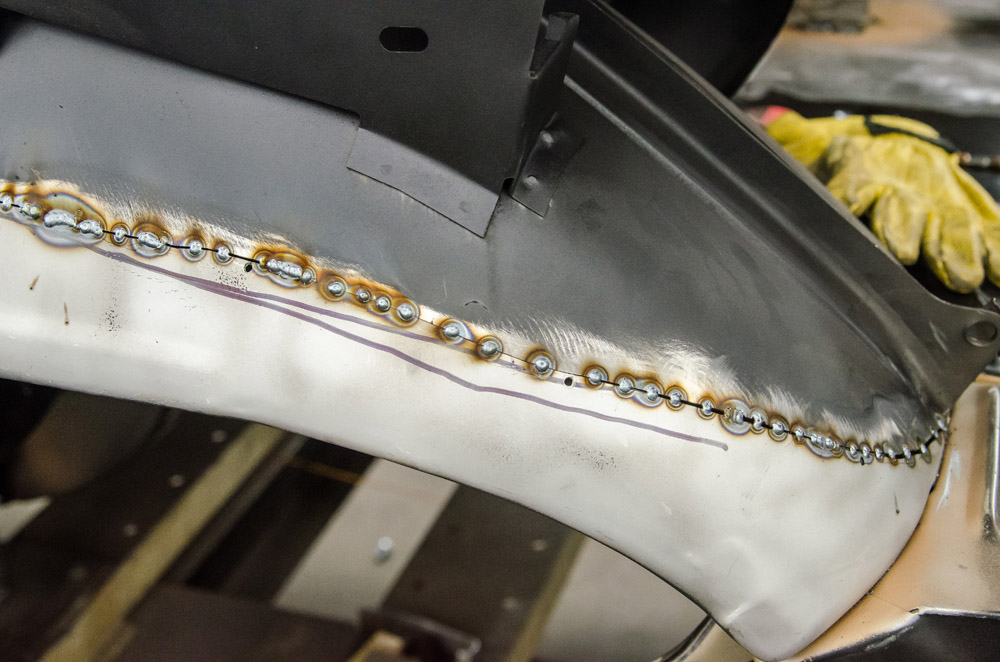

With very few exceptions, such as being used to replace leaded seams, there is no place for body filler as part of metal repair. (Not counting standard skim coating which of course is part of normal body work) All metal repair and/or replacement should be essentially seamless. The body should basically appear to be in the same condition that it was when it originally rolled down the assembly line. Isn’t that, after all, what getting a car restored is all about? Not just cosmetically but structurally, practically returning it to like new condition.

The process to getting to that end result starts with the car at a frame shop that MCR has worked with for many years. The car is rigged on a frame rack and its dimensions are checked just like would be done for any car that’s been in a collision. This will tell MCR if the car is straight and true or is, for any number of reasons, out of factory specifications. If it’s not within spec then the frame shop pulls it back into shape. It’s pointless to go to great lengths to preserve the cars dimensions if those dimensions are wrong to start with and the only way to tell is to accurately measure it.

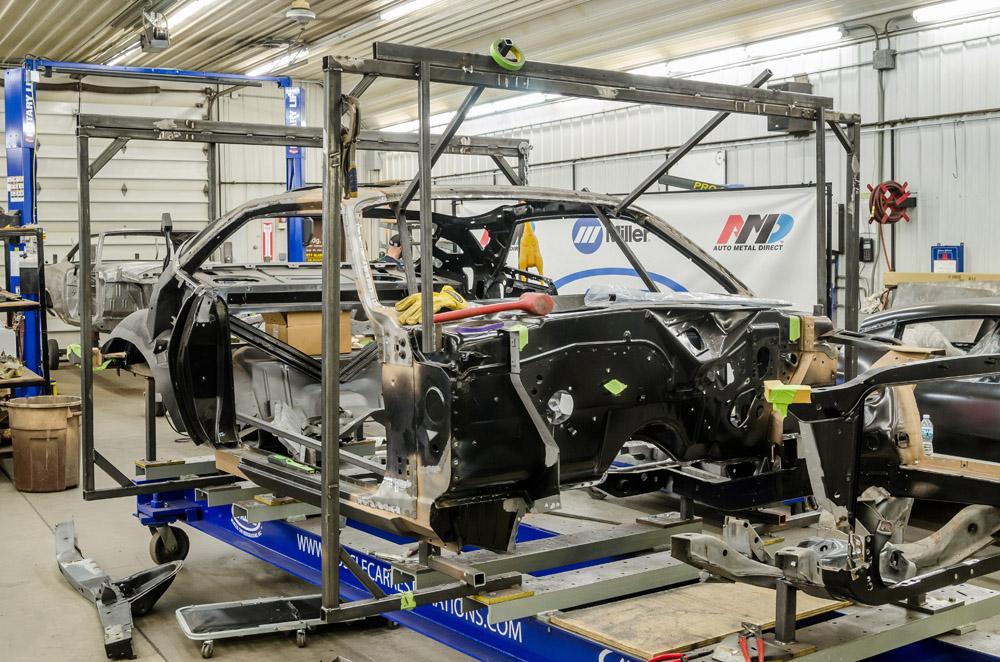

Once John’s Cuda was confirmed to be straight and within spec, his car was then literally welded to a frame table at MCR to guarantee that it will stay that way. In addition, halo style bracing was placed around and even inside the car, based on the sheet metal repairs that are needed, to further guarantee that critical parts don’t move out of place as the various sheet metal panels and parts are removed, and/or repaired and replaced. Once repairs are complete, the car will go back to the frame shop to reconfirm that it’s still within spec.

The actual metal work itself falls into a few different types. There are bolt on parts such as front fender, hoods and trunk lids that are, well, simple bolt ons. These are relatively simple to replace though there is a certain amount of patience required to get them to properly line up with the surrounding parts.

There are whole part replacements such as door skins, rear quarters, floor pans, roof, etc. These are parts that are replaced in their entirety. The whole part is removed and the complete new part is then usually spot or plug welded in place. Part placement generally needs to be precise though some are more or less so.

There are partial replacements where only a portion of a panel is replaced by splicing a section of a new part onto the good section of an original one. Wheel tubs are a common splice repair as can be quarters, floors and rocker panels among others. Many times only a portion of a part is rust damaged and it’s simply more efficient, and it preserves more of the original car, to only replace the damaged portion. There are also repairs that are best done by fabricating new parts from scratch. Some would call these patches but that is not really an accurate description. They are rarely a simple flat shape but rather they are formed by bending, shrinking/stretching, rolling into a precise replacement part. This is done mainly when there is no replacement part available or when rust damage is minimal and it would be beneficial to preserve the rest of the part intact. Just like any other, these should be entirely seamless repairs and should be virtually undetectable once completed.

Metal Work Videos

Sources

| Auto Metal Direct | http://www.autometaldirect.com/ |

| Miller Welding Equipment | https://www.millerwelds.com/ |

| Muscle Car Restorations, Inc. | https://www.musclecarrestorations.com |